An excerpt from Lafcadio Hearn’s short story (from the original)

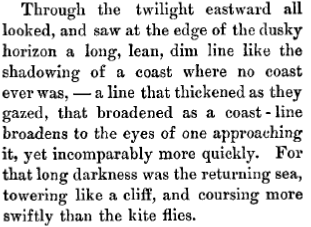

An excerpt from Lafcadio Hearn’s short story (from the original)

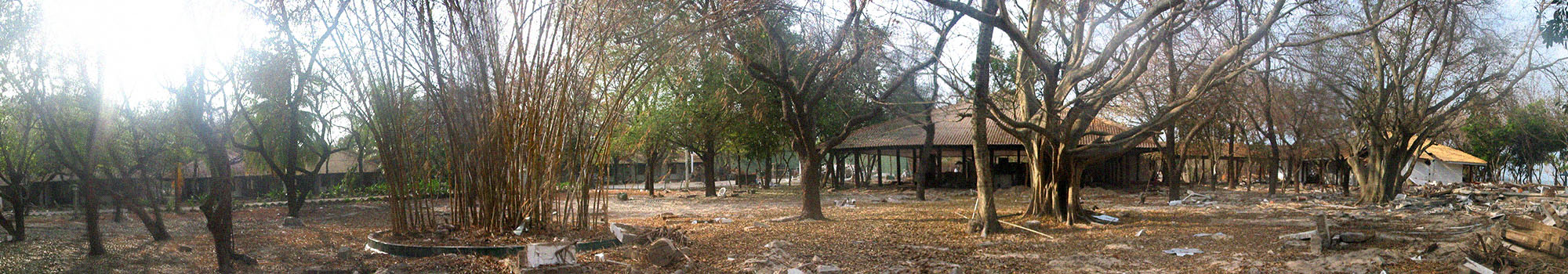

The story of Hamaguchi in a 1937 reading book for the Nakai Tsunezo primary schools and in a contemporary booklet

Thomas Jaggar at work at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (Courtesy USGS)

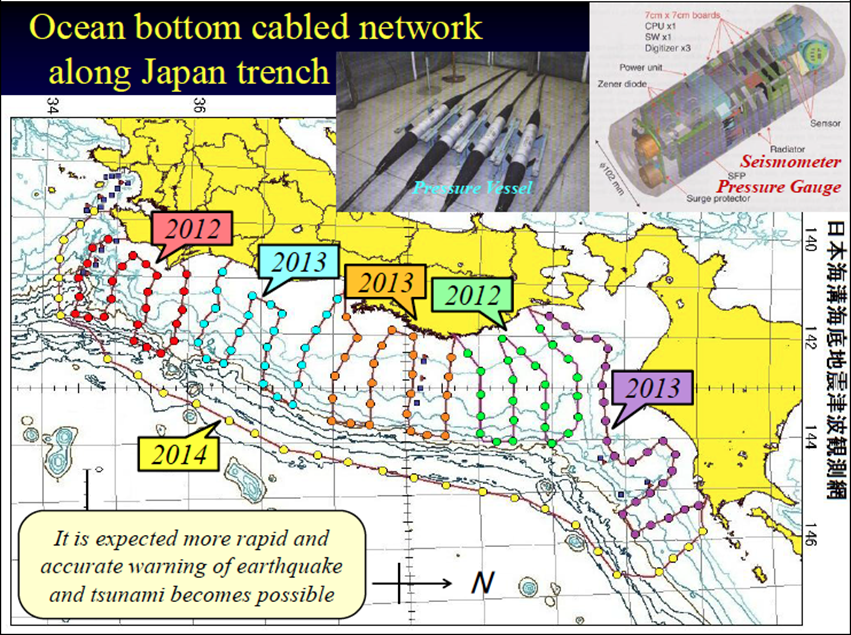

Implementation of the underwater seismographic network on the Japanese coast after the 2011 tsunami

The modern idea of alerting people to incoming tsunamis to allow them to save themselves dates back, in the first instance, to a historical episode in Japan during the nineteenth century, known as “The Fire of Inamura (Rice Sheaves)" (Inamura no Hi). As is often the case with episodes of great heroism, the story has become almost a legend and for this reason there are countless versions, each with different details. The most famous is certainly the one written by Lafcadio Hearn, a writer, journalist and scholar of Irish origin who was, among other things, the first foreigner to obtain Japanese citizenship, marrying the daughter of a Samurai and adopting the name of Yakumo Koizumi. According to Hearn's short story, published in 1896 in The Atlantic Monthly magazine under the title "A Living God", Gohei (Goryo) Hamaguchi was a wise and influential man, who during his lengthy life had long been a village leader.

On an autumn evening, from his hillside house he noticed a strange movement of the sea, which retreated, leaving beds of seaweed and fish uncovered, to the amazement of the villagers, who ran to the beach to see the unusual spectacle and were unaware of its meaning. Hamaguchi, realising the danger, understood that he would not have time to run to the coast to sound the alarm, and began to set fire to the sheaves of rice laid to dry after the harvest, to attract the attention of the hundreds of people who were at that time near the coast. These people began to climb up the hill quickly, wondering if Ojiisan - the grandfather - had gone mad to set fire to the harvest. When they reached the hill, a very long and thin dark line began to be glimpsed on the horizon, accompanied by a noise louder than thunder which in a few moments reached the coast, wiping out everything in a single, immense cloud of foam and vaporised water.

Later Hamaguchi had the first protective embankment built in Hiro-Mura to defend it from tsunamis, paying for it out of his own pocket: it was a five-metre-high and almost twenty-metre-wide dam, whose construction began in 1855, less than a year after the tsunami. Rocks, tsunami deposits and soil were used to build the dam, and rows of pine trees were planted to anchor the ground. That embankment, which still exists, was the first of many others, built along all the Japanese coasts, some of which are clearly visible in many shots of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami. The story of Goryo (or Gohei) Hamaguchi refers to the great earthquake which struck Japan on 5 November 1854, known as the Ansei - Nankai earthquake, and is still told in Japanese primary schools to teach children to understand tsunamis and to learn to protect themselves.

To celebrate Hamaguchi’s heroism, and especially to remember the risk of tsunamis, statues of Hamaguchi running through the fields with two torches in his hands setting fire to the sheaves of rice have been set up in several Japanese cities.

Precisely for these reasons, 5 November was symbolically chosen to celebrate the "World Tsunami Awareness Day" (WTAD), a UNESCO initiative aimed precisely at improving awareness of the risk associated with these natural phenomena. However, Hamaguchi's intuition could not have been followed up from the point of view of providing warnings: in 1854 both the knowledge and the technology necessary not only to develop but even to imagine an early warning system were lacking, and as is often the case in the field of natural risk reduction, it was a new catastrophic event which made clear to everyone the need to improve scientific knowledge and to develop monitoring and early warning technologies in order to save lives.

Japan can be considered, with good reason, the cradle of modern early warning systems and of the science that studies tsunamis. In 1896, after the gigantic and catastrophic Sanriku tsunami, with run-up waves up to 38 metres high and 22000 victims, the Japanese Ministry of Education's Earthquake Prevention Commission published the first scientific article mentioning the earthquake as a precursor to the tsunami.

The first attempts at monitoring and early warning date back to the great Kamchatka earthquake on 3 February 1923, of magnitude 8.3. On that occasion, Thomas Jaggar, seismologist and founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, recorded the shock and estimated its intensity and distance: knowing the different speeds of propagation of seismic waves and of tsunamis, he was able to calculate precisely the arrival times. Jaggar gave the alert, but was totally ignored by the authorities. The tsunami arrived as expected by the scientist, causing great damage and at least one death. On 2 March 1933, it was Jaggar himself who again gave the alert for the 8.5 magnitude Showa Sanriku earthquake in Japan. On that occasion, the authorities took Jaggar's alarm seriously, allowing them to evacuate the most exposed areas and to save many lives, even though the flood had caused much damage.

The 1933 Showa Sanriku tsunami also triggered some major changes in Japan's risk mitigation system: the Earthquake Prevention Commission itself prepared the first Decalogue on tsunami risk reduction, and many of the proposed countermeasures are still the basis for Civil Protection agencies worldwide.

In 1941, the first tsunami early warning organisation, which could operate on the basis of instrumental earthquake observations, was founded in Sendai to protect the Sanriku coast. Researchers at the Sendai Local Meteorological Observatory had prepared a diagram based on the amplitude of the seismic waves and on the distance to the epicentre to determine whether there was a danger of a tsunami; the Observatory was capable of warning citizens within twenty minutes of the earthquake, through police stations, local radios and telephones. With the enactment of the Meteorological Business Act of 1952, the forecasting system was extended to the whole of Japan under the coordination of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which still coordinates seismic monitoring and the issue of rapid alerts.

On 1 April 1946, an 8.6 magnitude earthquake off the Aleutian Islands in Alaska triggered a huge tsunami which travelled at over 800km/h and arrived in Hawaii five hours later. Because of its particular geographical position (in the middle of the Pacific Ocean), Hawaii is particularly exposed to tsunamis originating along the entire ring of the Pacific. On that occasion, at Hilo, the wave front reached almost 14m in height, claiming 159 victims and destroying everything it encountered in its path. On that occasion no alerts were issued, and after that event it began to be understood that if a message had been sent those people could certainly have been saved, and the damage would also have been more contained.

Following that catastrophe, in 1949 the U.S. government founded the first Tsunami Alert Centre, at the Honolulu Geomagnetic Observatory, the first nucleus of what would later become the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre (PTWC), which is currently part of the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and which is still today a reference point for early warning systems operating worldwide. The U.S. warning system has developed progressively, also following the catastrophic tsunamis of 1952 (Tokachi earthquake - Oki), 1957 (Aleutian Islands), 1960 (Chile) and 1964 (Alaska) that led to the founding of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre (PTWC) in 1967.

The Chilean tsunami on 23 March 1960 gave a new impetus to the development of early warning systems: no one in Japan felt the earthquake, and the JMA did not give the alert. However, the tsunami waves generated by the earthquake travelled for many hours across the Pacific, and their arrival on the Japanese coast the next morning, with heights between 3 and 6 metres, totally took the inhabitants by surprise, causing a great deal of economic damage.

A further impulse to the Japanese system came from the tsunami of 2011, generated by the great earthquake of eastern Japan (Tohoku). Following this earthquake, many important studies have been carried out to understand the generation processes of major seismic events, while the tsunamis defence systems have been greatly strengthened.

The Mediterranean region, part of the ICG/NEAMTWS (link to the sheet) also has an early warning and tsunami risk mitigation system, which operates not only for the Mediterranean but also for the North East Atlantic (From Morocco to Norway) and the connected basins (Black Sea and Marmara Sea).

The NEAM system became fully and officially operational in 2016, with the accreditation of the four Tsunami Service Providers (TSPs) operating in the area: the CAT-INGV for Italy, the CENALT for France, the Hellenic National Tsunami Warning Centre for Greece and the Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute for Turkey. Recently (December 2019), the Portuguese Institute of the Sea and Atmosphere (IPMA) was also accredited as a TSP for the Eastern Atlantic.