The devastating tsunami generated by the Mw9.2 magnitude earthquake on 26 December 2004 at sea off the Banda Aceh region, Sumatra Island in Indonesia, was one of the biggest natural disasters of the last 100 years. The tsunami caused - according to some official estimates - the death of at least 230,000 people along the coasts of the entire Indian Ocean, up to South Africa; the waves, which in some places reached thirty metres in height, caused material damage for 14 billion dollars, forcing the evacuation of at least one million six hundred thousand people.

The Sumatra event highlighted two crucial aspects: first, with the increase in the density of populations living along the coasts, the level of exposure to the tsunami danger has increased compared with the past; second, with a view to mitigating the tsunami risk, an early warning system active at regional level and coordinated at international level could save many lives.

For these very reasons, UNESCO mobilised immediately after the 2004 event, not only to organise aid to the affected populations, but also to offer its support to the national authorities in order to organise more effective warning systems. The aim was also to improve the response capacity of the populations, in order to reduce the loss of life caused by tsunamis and at the same time to protect the activities which ensure the livelihoods of the affected communities.

Following the first declaration on 30 December 2004, the first of a long series of international meetings between scientific institutions and Civil Protection organisations, coordinated by the IOC (Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission), precisely a UNESCO commission, was held in Paris in March 2005. The objective of these appointments, which have now become periodical, is to improve knowledge of the phenomenon, refine the assessment of the tsunami risk, make the early warning systems increasingly more efficient and develop communication and training measures for at-risk citizens and communities, so that they should be prepared on risk mitigation measures to be adopted in case of an event.

In order to allow an improved understanding of the importance of these changes, it is necessary to explain that the effectiveness of the tsunami alert systems depends on many factors: in fact, there is a need for a continuous improvement of the scientific knowledge which allows to identify and characterise seismic sources capable of generating tsunamis, of the instrumental networks that allow both to detect and to locate earthquakes which occur at sea or near the coast, and to measure any tsunami waves; an additional effort must also be made in order to identify methods and procedures able to rapidly estimate whether an earthquake is capable of creating a tsunami or not.

Moreover, it should be remembered that tsunamis can have an impact at local level (limited to short stretches of coast of a single country), at regional level (the tsunami affects the coast of one or more countries) or at basin level (the tsunami affects the coasts of an entire ocean): for this very reason, the methods and standards for sending tsunami alerts, the modes of operation and the criteria to be adopted to develop early warning systems are coordinated and harmonised at an international level.

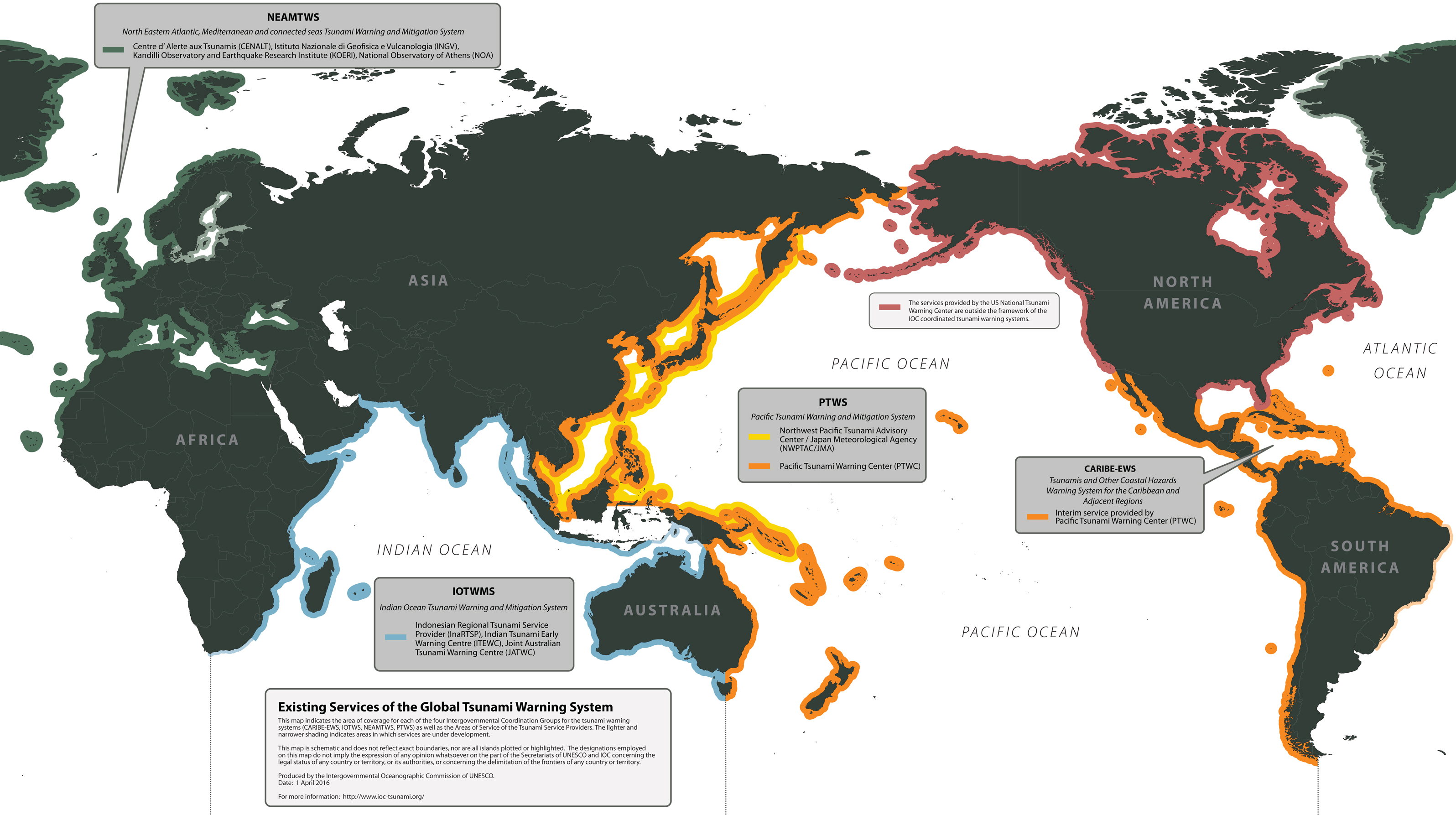

To better manage regional and global alerts, the IOC has adopted an architecture based on four subsystems which correspond to four precise regions: The Pacific Ocean (the first basin to implement an alert system), the Indian Ocean, the Atlantic area of the Caribbean and the North East Atlantic, the Mediterranean and connected basins (NEAMTWS).

The IOC regions for tsunami early warning systems

The IOC regions for tsunami early warning systems

Each of these areas includes the National Alert Centres (NTWCs), the Focal Points (TWFPs) which receive and re-launch information from one or more Tsunami Service Providers (TSPs), i.e. from the centres which carry out seismic and sea level monitoring seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. The TSPs have the task of distributing and disseminating alert messages to all other players in the system (governments, civil protection), both to the regional system and to the other organisations which have signed up to the service, thus making it necessary to have a set of procedures, formats and shared rules that allow information to be exchanged clearly, quickly and accurately.

The National Tsunami Alert Centres work closely with civil protection authorities and government officials to improve the ability to warn their citizens of the imminent danger of tsunamis caused by earthquakes in their region or from further afield.

Thanks to the on-going efforts of UNESCO and of the IOC, following the catastrophic events in Sumatra (2004) and Japan (2011), many important advances have been made, both in terms of scientific knowledge and in the ability to save lives.

However, it is important to remember that this work is characterised by a wide margin of uncertainty, which requires continuous verification and refinement, both to identify and resolve any problems of a technological or organisational nature, and to integrate and operationally apply the new scientific knowledge available. It is precisely for these reasons that the entire system is subjected to periodic tests whose purpose is to verify the functioning of the technological equipment (seismic stations, tide gauges, data transmission networks) and to verify the correctness and adequacy of the procedures.

Among the many tests envisaged, one of the most important is certainly the series of exercises called "NEAMWave", coordinated precisely by the IOC. The test consists in the simulation of the warning process on a regional and national scale, based on one or more pre-calculated scenarios which involve a hypothetical tsunami-creating earthquake in the area. On this occasion, the entire procedure is tested, with all the steps required in the event of a real event: from the analysis of the earthquake, the assessment of the potential tsunami-creating event, the issue of the alert messages, the real-time analysis of tsunami data, up to the application of the procedures for early warning by the Civil Protection organisations.

Drills are an important aspect of the monitoring work, aimed at identifying possible errors, improving operational standards and honing the speed and quality of the monitoring activities. Operators at all alert centres must regularly carry out earthquake-locating and message transmission tests to improve the system's response capabilities, in addition to large-scale drills such as NEAMWave, which periodically involve all alert centres and civil protection organisations in the area. The last NEAMWave drill was held in 2017, the next one will be in 2020.