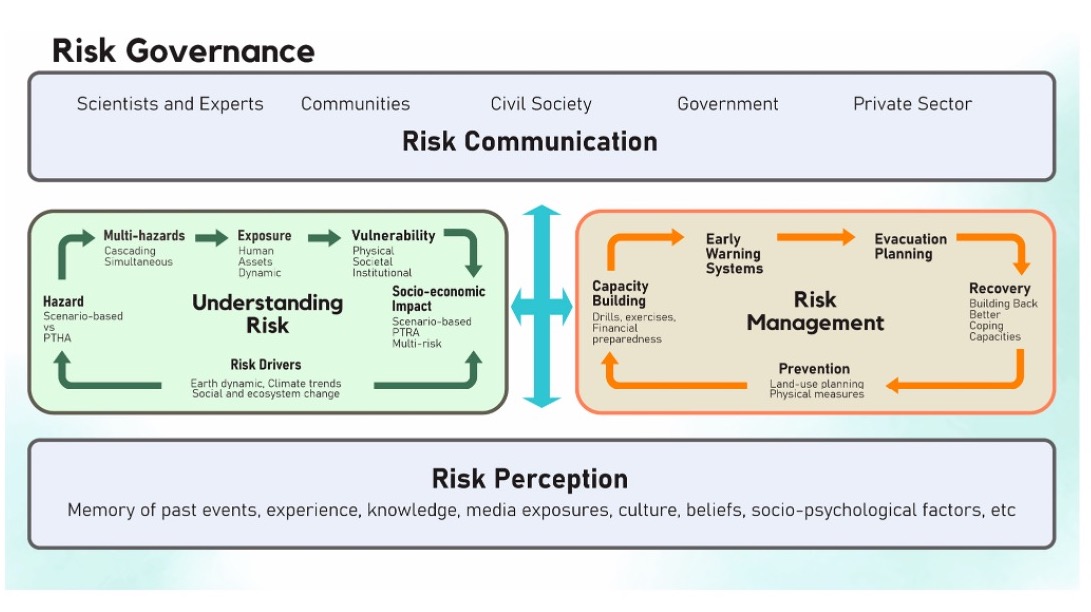

An integrated risk governance cycle for dealing with tsunami risk. It is important to acknowledge here that addressing complex and systemic risks is usually a (highly) non-linear process and cannot be properly captured by simple schematization with circular relations..

An integrated risk governance cycle for dealing with tsunami risk. It is important to acknowledge here that addressing complex and systemic risks is usually a (highly) non-linear process and cannot be properly captured by simple schematization with circular relations.. Irina and Fatemeh are the two first authors of the recent publication involving the research team of the AGITHAR (Accelerating Global science In Tsunami HAzard and Risk analisys) project with the wider COST Action (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) contribution entitled "Tsunami Risk Communication and management: Contemporary gaps and challenges". A scientific article that, through a thorough review of the lessons learned from past tsunamis, identifies the multiple challenges that still exist in the field of tsunamis and the gaps in risk communication. The paper identifies the study of probabilistic tsunami hazard and risk analysis as a key through which better communicate science and plan more efficient risk mitigation measures. We have interviewed the first authors who will give voice to the author team that contributed to the writing of this paper.

- Irina and Fatemeh, can you help us to understand better, starting from the title, what is the goal of the paper?

Certainly! The paper brought together a number of scientists from different backgrounds and disciplines to address a challenging question: how well have we been doing, both communicating and managing tsunami risks, learning from recent events that happened throughout the world? Usually this is a question that comes from practitioners, civil societies, governments, or even communities with tsunami risks. However, this is in fact also a scientific question. The scientists are challenged to gain a deeper understanding of what are the root causes that shape and form our practices in communicating and managing risks today. In the tsunami realm, the situation is particularly interesting and unique. The uncertainties are high, the societal dimension is particularly relevant and the consequences could be devastating. The risk perception is often guided and conditioned by large and rare tsunami events. Nevertheless, smaller tsunami events occur quite frequently and they can also be damaging and lethal.

Through this paper, we are trying to communicate and detangle the complexities associated with the occurrence of tsunamis intertwined with the complex social system that make tsunami induced-disasters become so difficult to mitigate. Hence, the paper is trying to put on the table these matters and questions. We had to do an extensive analysis of existing literature in order to bring these complexities into light.

Although the paper is focused on the gaps and challenges, it also provides examples of good practices and suggestions for enhancements. We really hope that the paper can reach out to many readers worldwide and spark discussions for improvements.

- This work is based on the interaction between "hard" sciences (numerical, quantitative, and evaluative sciences) and "soft" sciences ( social sciences, sociology, communication, and law). Can we call this a successful multidisciplinary experience?

We think all of the authors highly appreciate the multidisciplinary interactions and experiences afforded by the long writing process that took more than a year. It was not an easy process I have to admit, due to the inter- and transdisciplinary nature of this work. For example, we did not find the earlier drafts convincing enough. Therefore, we decided to keep on working and improving the draft. This gave us more opportunities to learn from each other across disciplines. We learnt much more about dialogue, patience, listening, compromise and consensus. At the end of the writing process, we were also different; we learnt from each other and found new angles of looking at things that we had not explored before.

Tsunami science itself is transdisciplinary and can not be confined by a single discipline. Tsunami science is not at all merely of hard science’s concern.

However, most of us were trained to view tsunami science through a particular lens. From its genesis, to how it is propagated, and how the forces are measured, one could develop an understanding on how to calculate probabilities of occurrences. Other scientists would delve deep into the social meanings of tsunamis. While some observe tsunamis from how it historically changes the society. These are only to name a few. Therefore, it is natural that these different dimensions and lenses, including terminologies differently used, spark lively debates. We have spent so many hours and virtual meetings (held during Covid-19 pandemic) to learn about each other’s perspectives and arguments. At certain times, we could not reach an absolute agreement. Nevertheless, these debates were extremely valuable to bring together a more comprehensive understanding of tsunami science. Indeed, we have all learned a lot by collaborating and to be able to experience this entire process in the challenging time of Covid-19 pandemic is so rewarding.

- Many authors contributed to the paper, where did this idea come from?

Almost all of the authors are part of the AGITHAR community. We participated in several meetings, including the kick-off meeting held in Malta in October 7-9 2019 and also the last physical meeting before the pandemic breakout in January 14-16 2020, in Rome. Risk communication was among the topic discussed in these two meetings. The meeting in Rome, which were hosted by Società Geografica Italiana and Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) resumed with a consensus. We agreed to develop a scientific report on tsunami risk communication and management, which was intended to be part of Chapter 4 of the AGITHAR deliverables. Later on, we decided to reshape and submit the paper to a peer-reviewed high impact journal to allow wider access to the paper. Along the way, we were convinced to bring together and unify tsunami risk communication and risk management as part of an integrated risk governance process. The idea of an integrated risk governance process is not new by itself and has been advocated by prominent figures in the field. However, it took us a lot of effort to bring together the two spheres of tsunami risk communication and management together in a tangible and relatable manner.

- There is a diagram - in the introduction - that describes the risk governance process for tsunamis and focuses on two key aspects: risk communication and risk perception. Are the two issues being properly weighted? What is emerging from this study?

This is a particularly important question and is also central to the writing process. One of the main concepts the paper is emphasizing (as you mentioned also visually) is the two-way relation between risk communication and risk perception –as two dynamic processes that affect and shape each other in a reciprocal manner.

The social science group within the authors team were keen to address a critical reflection of risk communication, not merely as a prescriptive tool but as a central and pivotal process within risk governance. For example, risk communication is particularly challenging when communicating probabilities and uncertainties. Another example regards the link to risk management. Often, the discussions on risk communication tended to detach from the risk management cycle, and risk perceptions were vaguely related to risk assessment and management. This paper argues that these important means and processes greatly influence one another. It is paramount to understand this, as the complexity of tsunami events continue to increase, along with increasing urbanizations, digitalization and rapid social changes. We intend to explain that the relations between understanding risks and managing risks are strongly and actively influenced by risk communication and risk perceptions. These relations are not linear, but rather, complex and interrelated.

By proposing such an argument, we are quite convinced that we have addressed risk communication and risk perception in proper weight.

- A saying goes: "history teaches". Our current knowledge about tsunamis are based on events that happened in the (more or less recent) past. Does the same apply to different cultural and territorial contexts? Or do differences between them emerge?

This is a good question. To answer it, we need to consider several factors. Certainly the hazard of the reference area, the occurrence frequency of events, and how the local community has responded to past events. These factors determine a community's resilience to tsunamis and more or less ensure emergency preparedness. There are cultures that, given the hazardous nature of the territory and the frequency of tsunamis, have learned and assimilated in their customs some hereditary traits. For example, Simeulue culture that through popular songs linked to actions, as we have seen in 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, was able to face almost autonomously the tsunami threat. They are able to understand the tsunamis precursors and issue warnings through word of mouth. In contexts such as the NEAM area, the low frequency of tsunamis has left fewer traces in local communities' memories. This makes the population more vulnerable even if the context of reference is more technologically advanced. Where the tsunami frequency of occurrence is low, proper attention is not given to the risk they pose.

- In summary, what are the biggest challenges to improving the gaps emerging in the paper?

Among the most challenging aspects of the paper is to address the uncertainties of events in a continuously changing society. It took courage, time and energy to think and discuss about how probabilistic approaches can effectively address these challenges, and what that would mean for risk communication and management. We are in a moment when the understanding and proper application of PTHA/PTRA, are still restricted. This is in part due to limited availability of relevant infrastructure and resources. On the other hand, users such as local governments are often hesitant to develop disaster risk management planning with too many options in hand as PTRA would suggest. At the moment, PTHA/PTRA for example are more favored by insurance sectors. But we are convinced that this will change in the future, propelled by the advancements in computational power and technology. With this in mind, we are convinced that we should continue encouraging progressive development of risk communication and management, including all the relevant branches of research.